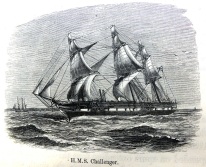

The HMS Challenger voyage was massive. A four year long trip around the world is not going to go without ups and downs. Here are some of the sad and unfortunate deaths of the crew as the years went by.

18th November 1872 – Challenger at Sheerness, Kent

Let’s start right at the beginning. HMS Challenger started off in Sheerness to be refitted before going to Portsmouth. One dark night whilst still at Sheerness, a young man called Tom Tubbs was wandering up the ship’s gangway in the dark before tripping and drowning in the dock. Despite best efforts by shipmates and the police, poor Tom could not be saved. Could this have been a warning that the voyage would not go as smoothly as imagined?

25th March 1873 – Station 24a – Challenger between St Thomas and Bermuda

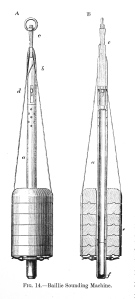

Early morning at 6.15am the ship got ready to sound and dredge. At 11.10am a dredge was put over but little did they know that when hauling in the dredge one of the hooks holding an iron block to the deck would break, sending the block flying and striking a young sailor, William Stokes, to his death. And it wouldn’t be much longer until tragedy struck yet again.

4th April 1873 – Challenger at Bermuda

Once the crew reached Bermuda they came across a beautiful picturesque harbour at Grassy Bay, not far from the capital of Bermuda. The atmosphere between the crew had just started to change for the better and so it must have been horrific for Richard Wyatt, the ship’s writer, to hear the dying gasps of the ship’s schoolmaster and find him dead due to a stroke. He was put to rest at a nearby cemetery in Bermuda.

28th June 1874 – Challenger on route to New Zealand

The next death recorded was some time after Bermuda. On route to New Zealand, nearly at the harbour, Edward Winton was out to do a sounding when the sounding cable got caught. He went to free it from the anchor when a huge wave of water struck the ship, knocking poor Edward into the sea, never to be found.

13th September 1875 – Challenger on route to Tahiti

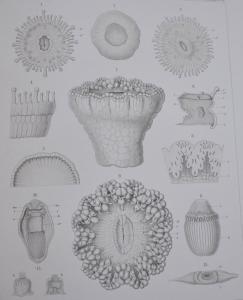

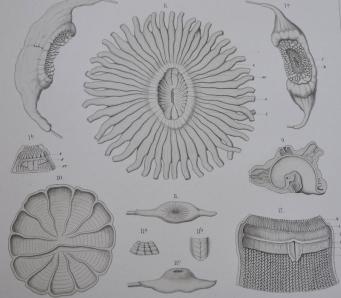

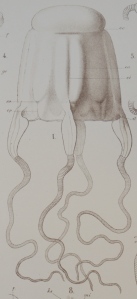

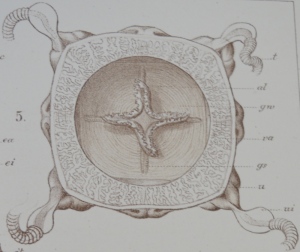

Dr Rudolph von Willemoes Suhm, born September 11th 1847, joined the Challenger at the age of 25 as a naturalist. Moseley was very fond of him – learning a lot from his knowledge and proud of his enthusiasm for zoology. Sadly, Suhm got erysipelas, a bacterial infection that attacks the skin and died at the age of 28. It was a sad time for all.

23rd January 1876 – Challenger at the Falklands

Nearing the end of their journey, despite being very happy to be on the Falklands and drinking to celebrate, a young sailor fell overboard. This young man was popular amongst all and was planned to be married when the voyage was over.

So there we have it – and there were probably far more deaths that aren’t recorded as well as illnesses and disease that riddled some of the crew. There are also some stories in the diaries that give us an insight into the world of the locals too. In Fiji, when highly regarded visitors went to see the great chief, the visitor had to bring human flesh, usually of a prisoner, just for fun. If there were no prisoners the visitor had to go out and find others to kill for the chief – usually a lone girl or woman. Horrible to believe how some people used to live!

Project update

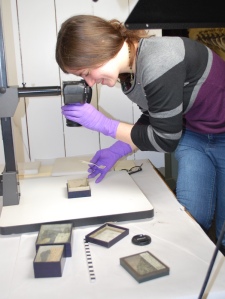

Regarding the Challenger project, I had a successful Scotland visit – seeing the Hunterian in Glasgow and the collection centre at NMS, taking lots of photographs for the database. Great fun and such a lovely bunch of people! Holly has also had a great trip to Manchester. Just another few months before the database goes live! To help us with this, we welcome our new volunteer, Peter, to the Challenger team! Here he talks a little bit about himself and his interests in the project:

“I am a history student at the University of Exeter. This project is interesting to me because, as a student, I very much appreciate it when online archives I use in my research are well organised and easy to access. This will be a great insight into how the archiving process works. As a tech enthusiast I am always interested to see my degree and my interests used together to help our knowledge of the past. Now that my exams are done I look forward to getting involved behind the scenes at this great museum!”